The Hidden Problem of Contaminated Packaging

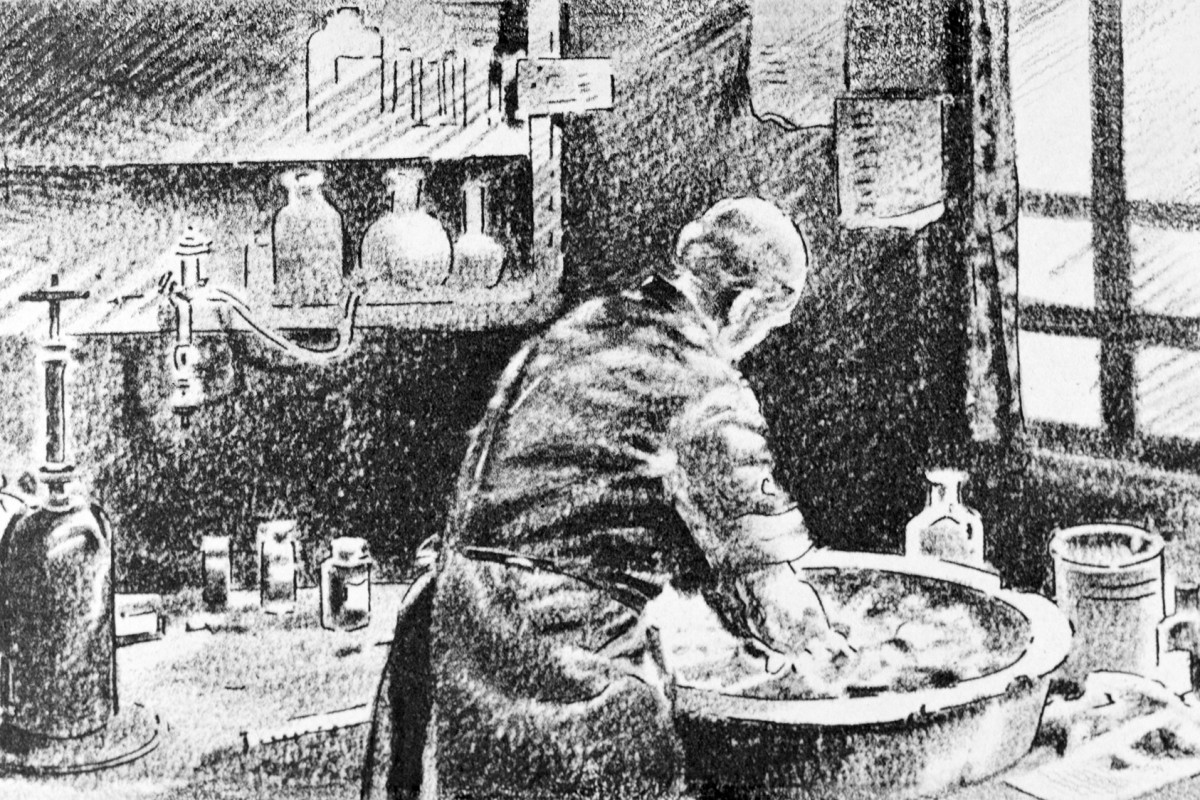

The history of science reminds us that theories we take for granted now may very well have been dismissed when first proposed. The case of Ignaz Semmelweis is one such example.

In the 1840s Ignaz discovered that babies delivered by doctors had a higher mortality rate than babies delivered by nurses. He identified a clear link between doctors’ lack of hand washing and higher death rates. Doctors assumed they were cleaner than patients and nurses and did not wash their hands prior to delivering a baby, even if they had just come from an autopsy! He discovered that the use of hand disinfection in obstetrics clinics could significantly cut the incidence of puerperal fever, a major cause of infant death.

The discovery of the importance of hand disinfection was not accepted at the time and Ignaz was ostracised by the medical profession. Worse still, despite his protestations that he could help save lives, Ignaz was eventually committed to a mental institution where he was beaten to death by his “carers”.

Not the jolliest of stories I know, but one that mirrors my own strong convictions about why Campylobacter is still responsible for 80 per cent of food poisoning cases, kills on average I person every three days, and leaves many others with longstanding health problems.

The FSA should be praised for their efforts in publicising data on the prevalence of Campylobacter in chicken bought from UK retailers, but the data, in my opinion and in view of many others, has been interpreted incorrectly.

The headline figure of 80 per cent contamination of fresh chicken draws media attention but whatever the contamination level the public should be careful when handling and preparing chicken. FSA advice to follow the 4 Cs of food hygiene, cooking, cleaning, cooling and avoiding cross-contamination, should be observed.

The FSA figures have shown consistently that up to 7 per cent of the outer packaging of chicken is contaminated with Campylobacter. Our own consumer surveys show that the public are just not aware of this danger and, when told about it are very surprised and ask why this is not highlighted.

What seems to have muddied the water is that detailed analysis suggests that only 1.4 per cent of packaging is contaminated to a level that reaches the infectious dose for Campylobacter. The low figure makes the problem seem small and leads to it being ignored.

But given the vast amount of chicken purchased, extrapolating the figures means that nearly 9 million packs of chicken per year are contaminated to a level that could cause illness. This fact shouts as loud to me as poor hand washing did to Ignaz.

So what is being done?

There are lots of initiatives in processing plants to reduce levels of Campylobacter directly on chicken. But as it is cut, prepared and packed in an industrial environment the level of bacteria on outer packaging is often high.

Some experts suggest that the risk posed by contaminated packaging may be much higher than identified by the headline figures. Campylobacter is prone to die off over time but (stronger) survivors can still contaminate hands, other food stuffs, and with increasing use, reusable bags.

In a recent study Aston University found that Campylobacter bacteria were still present in reusable bags after 8 weeks and it took 16 weeks for them to disappear completely. In a 2007 study in San Francisco, when reusable bags were introduced by law, hospitalisations from food poisoning increased by 47%. Given these findings we are concerned about the potential impact of the newly introduced levy on disposable carrier bags on the incidence of foodborne disease. Positive, preventive, action by the likes of Marks and Spencer to use only Biomaster Protected reusable bags, which will inhibit the growth of microorganisms including Campylobacter, should be applauded.

Ignaz’s recommendation eventually led to the development of chlorinated hand washing, but only after his death. I don’t want to wait that long, there are things that can be done now, easily and inexpensively, to reduce the public health risk posed by contaminated packaging.

Should we tell consumers to wash their hands after shopping? Should we double bag chicken in store? But then how do should product be handled to get it inside the bag? Or should we use technology, such as Biomaster to address the problem?

I know what I would recommend, but you may think differently. Whatever the answer we must not ignore the problem. The risks from 9 million contaminated packs are too great.

This article first appeared in the July edition of Food Pulse, the monthly newsletter of TiFSiP (The Institute of Food Safety, Integrity & Protection

← Back to blog